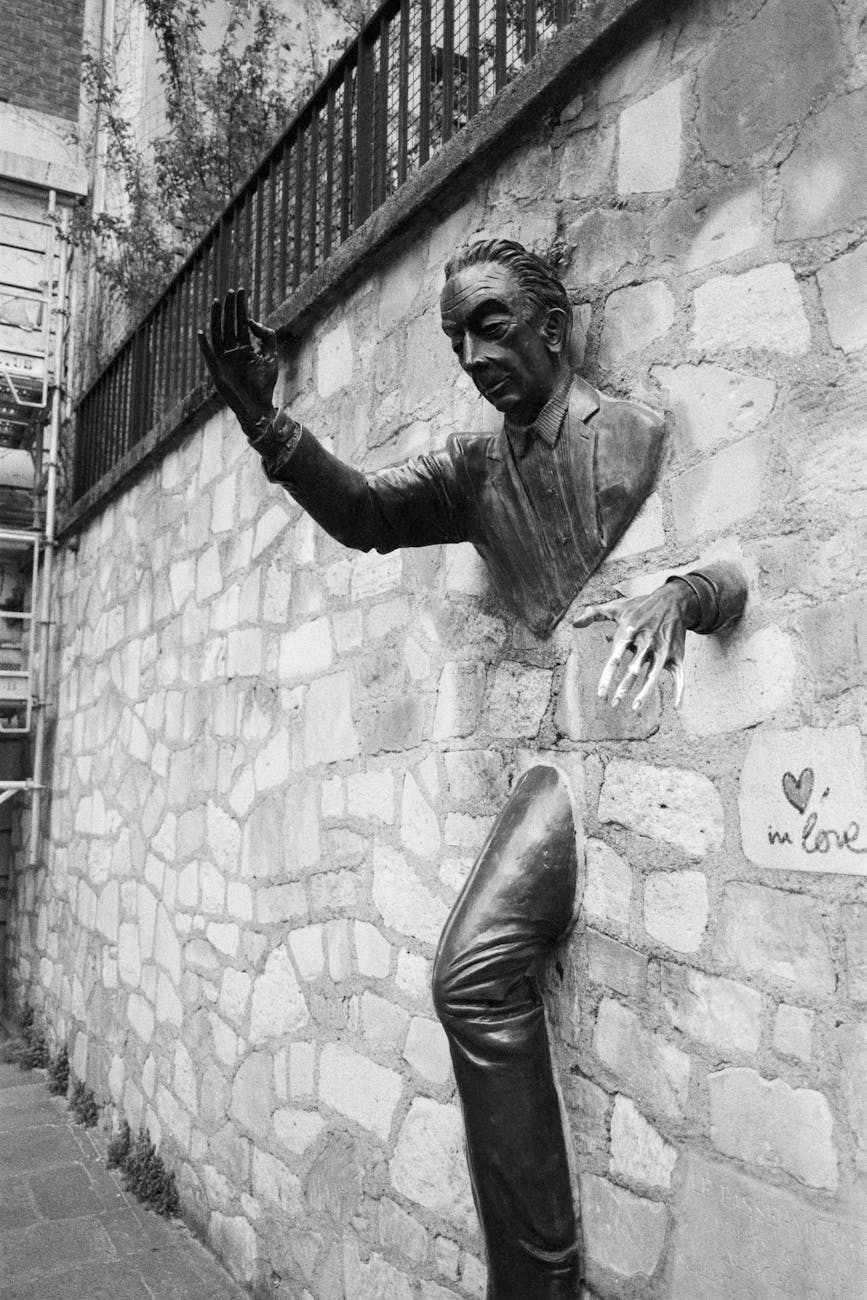

Badiou stated there are generally four philosophical conditions to be scrutinized: science, art, politics, and love. While most of them pursue truth and order, love—in my opinion, is different. Love has power over the truth and order: people act vastly paradoxically, ironically, and differently upon the same ‘reason’. In a way, love is a force of explanation, an ontological challenge towards being and becoming, scrutinized by the whole ideological spectrum, utilized as a force of change or even preserving values. An ultimately absurd condition that makes philosophy either a cosmically solipsist ethereal thought or a dumb play on human reasoning.

To differ from sentiment, love puts said sentiment in motion: love is something more conceptual—similar to Socratean Forms—than sentiment; sentiment, on the other hand, makes love reasonable. Hence, since sentiment existed, the attraction was made to bind love into its more substantial form. There are at least five different kinds of attraction: sexual, sensual, aesthetic, romantic, and platonic. And how do each kind of attraction foster sentiment and ultimately bind love into its conception, you may ask?

Each kind of attraction was made to match with our Id—our most profound, wildest, raw impulse and desire: to be delighted, to be touched, to experience beauty, to belong, to function. Our impulses, hence, require the Other self to be controlled—ultimately to fulfill our Being: and this is where the attraction comes, and then we reason and justify our acts through sentiment, while love, without explaining itself, becomes an inherent part of our justification. Let me present you an example: a romantic attraction, to put in a simple phrase, is a desire to date someone (or something, I guess, no judgment). It happened because we crave to belong; we evolved to the point when it’s physically damaging to be in constant solitary. But, our desire to date someone has to be based on something. We search for justification—which, even if it’s entirely personal, won’t really be detached from the social vacuum (or construct, but we are not here to talk about dialectical/historical materialism, yet). Our justification becomes the basis of our sentiment. We express our justification with language: we love because we can express our love.

At least, that’s what I thought. Simplified.

Pointing out the difference between sentiment, attraction, and love is important: my take involves heavily personal experience, which shapes my opinion towards love as a whole concept. I am not trying to theorize love into a valid thesis. Hence the title ‘uninformed’ is being used. So, where to begin?

First of all, I hate dating games. Especially here. Specifically here. I got the gist of being subtle and yadayadayada. Still, the dating scene here is too subtle: even on a sociological level, considering their local wisdom is quite prudish, which makes them hide their intention. I am complaining if the potential significant other was playing Morse or Invisible Ink (to let it slow-burn to read the message). And guess what? I don’t have the time. But to put an intention forward is considered creepy, which doesn’t make sense—but yeah, the repressed world we live in is indeed scary.

To dwell deeper into something more personal to discuss, “to love, to watch-think-seek the other in the other, to despecularize, to unhoard. Does this seem difficult? It’s not impossible, and this is what nourishes life—a love that has no commerce with the apprehensive desire that provides against the lack and stultifies the strange; a love that rejoices in the exchange that multiplies [sic].” Helene Cixous in The Laugh of the Medusa apparently had a difficult time to conclude her own question, “does it seem difficult? It’s not impossible,” because whenever someone brings up the notion of altruism in love, they aren’t always sure if altruism is part of a relationship conceptually or love in general. Personally, I don’t believe in altruism. There is always quid pro quo, a ‘commerce,’ either fueled by mere sentiment or involving an actual accountant. As I said, even sentiment is not pure; it exists because our desire must be regulated—if not repressed. Hence, we always expect something as feedback. We don’t ‘watch-think-seek the other in the other’ to put ourselves outwards—we are inherently narcissists, even with our empathy. We watch-think-seek the other because we (don’t) want to find something in ourselves. We duplicate, and we face Other to find Ours.

Hence, even though I call myself a hopeless romantic, paradoxically, I despise sentiment—or, more like, despise the notion of altruism while disguised as sentiment. It doesn’t feel authentic; it’s ‘unethical’ in a Kantian sense.

Leave the Form and enter the substance. To quote Childish Gambino’s words, “What kind of love?” Culturally speaking, the manifestation (or…infestation?) of love defines our conception of a relationship as a whole, e.g., marriage, dating, with benefits, et cetera. We involve ourselves with Others, perhaps not knowing how the dynamic came to be. For a cisgender heterosexual male—like myself, history aligned to our needs and our needs only, hence creating disparate power dynamics between gender relations. I think this is known, though. My take on the relationship as an idea is to constantly reassess power structure, to learn feminism as an atonement for collective historical sins, to pick on patriarchy as a system to the ground, and to reconsider if our needs are essential to be compensated systematically.

Man’s happiness today consists in “having fun.” Having fun lies in the satisfaction of consuming and “taking in” commodities, sights, food, drinks, cigarettes, people, lectures, books, movies—all are consumed, swallowed. The world is one great object for our appetite, a big apple, a big bottle, a big breast; we are the sucklers, the eternally expectant ones, the hopeful ones—and the eternally disappointed ones,

― Erich Fromm in The Art of Loving

In the end, apparently, I tend to make a relationship into a reassessment lab: to constantly challenge gender roles and issues, to put chivalry and masculinity into question, and ultimately to be comfortably vulnerable around the Other. Though I suffered from anxiety from either restraining or releasing myself too much or too little.

Lastly, I always thought partner should share their bitterness towards late capitalism and conformity, “Most people are not even aware of their need to conform. They live under the illusion that they follow their own ideas and inclinations, that they are individualists, that they have arrived at their opinions as the result of their own thinking—and that it just happens that their ideas are the same as those of the majority,” said Fromm in The Art of Loving. In short, a relationship should be as punk as possible.

And that’s why I think relationships—as love manifested—should grow beyond a person to be Tyler Durden and Marla Singer at the end of Fight Club.

The problem with my take and its implementation is I became a selfish lover. I seek growth within myself through the Other without considering the Other’s feelings (and growth). I deliberately alienate myself and the Other: by constantly questioning stuff around. I don’t know if this is healthy, but it makes me lonely. Incapable of loving organically. And distant. Though I tried to understand Others’ sufferings and profound dissatisfaction, as Nhat Hanh advised, I failed because I only looked out for myself. I always do.

People do not see that the main question is not: “Am I loved?” which is, to a large extent, the question: “Am I approved of? Am I protected? Am I admired?” The main question is: “Can I love?”

― Erich Fromm in Love, Sexuality and Matriarchy: About Gender

Leave a comment