First Published in Saturasi Zine Vol. 15: Politics (October 2023) in Indonesian.

Rob Rogers, an editorial cartoonist for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, was fired from his job after 25 years for being ‘too angry’. His cartoons, which often made fun of Donald J. Trump, the 45th President of the United States, were the cause. Rob certainly laughed when interviewed by The Daily Beast1 in June 2018. “I’m not an angry person,” he said.

Rob’s work in the last week before he was fired was often rejected by his superiors. However, Rob was adamant and adhered to the principle of ‘take it or leave it’ when it came to his cartoons. On June 5, 2018, Rob’s last cartoon in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette was published, which made fun of supporters of Trump’s policies in the 2018 United States-China Trade War. Even after being fired, Rob will continue to draw, “I don’t want to use the word ‘angry’ because someone might accuse me of being ‘too angry’. What I work on is what bothers me and bothers you, what makes you say to yourself, ‘This is unacceptable, this is unfair, I need to draw this,’ and in the Trump era, that’s often about Trump himself.”

Laughing at Politics

Quoting the introduction to Antara Tawa dan Bahaya (Between Laughter and Danger) by Seno Gumira Ajidarma (2012), Danarto said that cartoonists are none other than politicians armed with images. This weapon becomes sharper in situations and eras that are not fertile for the growth of criticism. Offense, laughter, and other affective responses after reading a cartoon prove that images, like other texts, carry the burden of ideological meaning. Moreover, if the cartoon itself openly offends power.

Power then also outlines how the language of criticism is conveyed, including visual language. Criticism of power is conveyed depending on the type of power at work. The delivery or communication of this criticism can be parallel to the regime, or radically diametrical or in opposition to the desire for power. As in the New Order era, Mundayat (1991)2 noted the proclamation of the mythology of the ‘wawasan nusantara‘ (archipelagic perspective) by the regime which emphasized manners and inner political currents.

One of the most obvious implications can be seen in Panji Koming, an editorial cartoon by the daily KOMPAS which was born in the midst of the New Order regime, precisely on October 14, 1979. Dwi Koen, as the cartoonist of Panji Koming, then worked on his cartoon with a veil of euphemism, with a story full of metaphors, and a purely allegorical premise: by making the feudal era the background of the characters’ stories. However, this is where the ‘cunning’ of a cartoon lies3: in Dwi Koen’s defense, the feudal background in Panji Koming is a narrative device to mock the power that claims to be democratic.

The humor in the way of mocking power continued after the New Order regime fell. However, instead of talking through a veil of metaphor that was cleverly hidden, Panji Koming in the early reform era became bolder by adopting a caricature storytelling technique. The political figures discussed also became Panji Koming figures and characters. Feudalism is still the very setting, considering that the premise of Panji Koming is none other than the discourse of power in democracy as the subject of ridicule.

The shift in visual storytelling techniques marks a shift in the regime or ideology as a field of critics. This then emphasizes that even in different fields, cartoons continue to work and are burdened by their ideological meaning. As editorial texts, cartoons are surrounded by newspaper business interests, journalistic mandates, and partisanship. Of course, this encirclement builds the foundation of meaning, where language—including visual language—works.

Visual language in comics is, ultimately, just another language. It is inseparable from it’s arbitrary nature and convention. The plastic organization4 of how comic language is read—and ultimately, the need for drawing techniques in conveying messages, i.e. the use of caricatures in Panji Koming, is a decision that cannot be separated from how the regime regulates the language of critics. The matter of fighting radically, following it cleverly, or following blindly, again, is a matter of how cartoonists—as the conveyors of comic language, decide to take stands and compromise.

However, criticism does not always have to have a special world-building as an arena for discussing power. In cartoons, criticism can then become literal and gut-punching by juxtaposing the logic of power with the world of children and their innocent criticism. Politics always has a way of explaining itself in a complicated way. Where in fact, politics own behavior and actions are no less childish when it is then discussed.

(Re-)Shifting Language

SAFEnet reported that at least 132 people have become victims of the ETI Law and the defamation/libel article throughout 2020-20215. The implementation of this law has been proven to exist to protect the status quo rather than to maintain diversity. The reporting authority always has more power than the one being reported. This unequal power relationship confirms that the law then becomes a tool to repress freedom of speech—which is a basic right—and to blunt criticism.

The most obvious consequence of the repression due to the ETI Law is the self-censorship that is often found on social media. The country that are clearly criticized are then shrouded in the terminology of fictional countries such as Konoha (from the Naruto manga by Masashi Kishimoto) and Wakanda (a fictional country located in Central Africa from the Marvel Comics universe). Comic texts, although in themselves do not specifically discuss countries, then become catharsis to discuss power.

This language (of not just) visuals also shifts when discussing power. Democracy then became as a common term as a mere copy, not a practice with the burden of ideological meaning worthy of fighting for equality. Under the guise of being held once every five years, citizens and denizens still talk timidly about power.

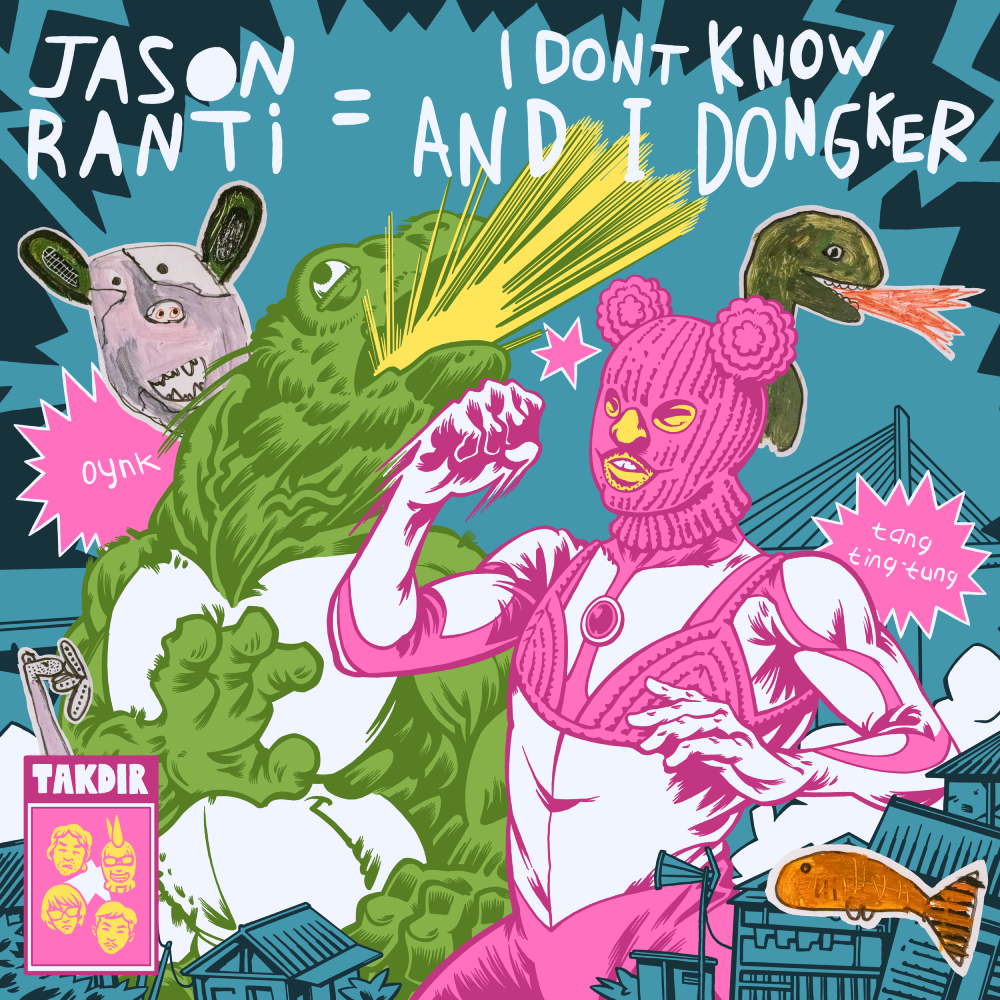

Even so, there are still several cartoonists and artists who discuss power openly. Gump ‘n Hell is one of them. Their critical comics discussing the actions of those in power may be a shield of reason for the courage to discuss politics openly—such is the ideal of democracy.

Although, yes, like the cartoon he worked on above, the worries and fears are still there.

- Grove, Lloyd. (2018, June 21). Rob Rogers, fired for his “angry” trump cartoons, fires back. The Daily Beast. ↩︎

- Mundayat. (1991). Alus dan Kasar: Komunikasi Politik di Bawah Orde Baru ↩︎

- Anderson, Benedict R’OG. (1990). Kuasa Kata: Jelajah Budaya-budaya Politik di Indonesia. Mata Bangsa ↩︎

- Kepes, Gyorgy. (1944). Language of Vision. Paul Theobald and Company ↩︎

- Juniarto, Damar. (2021). Revisi UU ITE Total Sebagai Solusi. SAFEnet. ↩︎

Leave a comment